It all started with a fundamental observation.

Childbed fever – a sepsis caused by bacterial infection – was common in the 17th century, and was responsible for about half of all maternal mortality [1]. It was thought to be caused by overcrowding, poor ventilation, the onset of lactation or miasma. In 1847, Ignaz Semmelweis ordered chlorinated lime handwashing before each examination, and the mortality rate dropped dramatically; from 18% to lower than 2% [2]. This was the first evidence that hand hygiene has a huge impact on preventing the spread of infections.

Thenceforward, several studies confirmed the importance of hand hygiene, and we selected some major ones to illustrate the effectiveness of hand hygiene.

Pittet et al. 1999 took microbiological samples from 417 healthcare workers, after they cleaned their hands. The 5 fingertips (that were imprinted onto the agar plate) carried an average 100 CFU bacteria. Although most of the bacteria were part of normal skin flora, 10.5% of the isolates contained Staphylococcus aureus, and 14.5% contained gram-negative bacilli [3]. Another study in a neonatal unit had similar findings; 13% of samples contained Enterobacteriaceae, 2.5% S. aureus, and 1.8% filamentous fungi [4, 5].

Casewell and Phillips 1977 found, that 17% of nurse’s hand were contaminated with Klebsiella spp in an intensive care unit. Hands got contaminated with 102-103 CFU Klebsiella even during “clean” procedures, e.g., taking blood pressure and pulse, or touching patient’s shoulder [4, 6]. Kac et al. 2005 recovered transient pathogens from 15% of healthcare workers hand when microbiological samples were taken immediately after patient care. After hand rubbing, no transient pathogen was recovered [4, 7].

Hayden et al. 2008 investigated the spread of VRE (Vancomycin-resistant enterococci). They described that of 103 healthcare workers whose hands were negative for VRE before entering the patient room, 70% contaminated their hand (or their gloves) by touching a VRE infected patient or the patient environment [8]. Tajeddin et al. 2016 took bacteriological samples in an intensive care unit from the patient’s environment. The most frequently contaminated objects were ventilators (83% of samples were contaminated), oxygen mask (82%) and bed linens (68%). Bed linens were contaminated with A. baumannii (35%), S. aureus (15%), S. epidermidis (12%, part of the normal skin flora) and Entrococcus ssp (6%) [9].

Barker et al. 2004 investigated the spread of Norovirus. A fingertip was artificially contaminated with Norovirus, then touch a series of surfaces without recontamination. In 25% of the cases even the 7th touched surface get contaminated with the virus [10]. Duckro et al. 2005 examined the spread of VRE via healthcare worker’s hands. Transfer of VRE from an infected patient of contaminated surface to another surface or patients via healthcare worker’s hands occurred in 10.6% of opportunities [11].

Hand hygiene guideline and recommendations agree that the most accurate way to evaluate the effectiveness of hand hygiene is finding its correlation to healthcare-associated infection rates, as an outcome. However, there is limited data available, since it is extremely challenging to measure this one factor correctly. The lack of control group is the other most common limitation. Arguably, during a hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign, it is hard to manage a control group. Without a control group, the seasonal variations, the influence of outbreaks, the placebo effects, etc. cannot be eliminated [4].

Pittet et al. 2000 implemented a hospital-wide hand hygiene program between 1994 and 1997. During this period, compliance improved (from 48% to 66%), alcohol-based handrub consumption increased (from 3.5 to 15.4 liter per 1000 patient-day), and overall HAI decreased significantly (from 16.9% to 9.9%) [12].

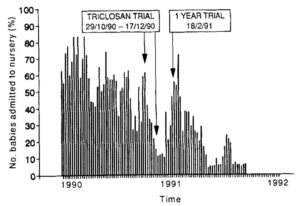

Webster et al. 1994 introduced a new hand disinfectant (1% triclosan) in a neonatal intensive care unit, what lead to significant fall of MRSA colonization rate. No other protocol or procedure was changed during the 25 months study period [13].

Figure 1.: MRSA colonization rate. Interventions: 7-week trial period with the new hand disinfectant, after getting permission, a 1 year trial period. (Source: Webster et al. 1994)

Zerr et al. 2005 implemented a hand hygiene program in a children’s hospital. Compliance improved from 62% to 81%, meanwhile hospital-associated rotavirus infection decreased from 5.9 to 2.2 episode per 1000 patients [14]. De Angelis et al. 2014 summarized 134 studies, addressed the transmission of VRE, and found that implementation of hand hygiene was associated with a 47% decrease in the VRE acquisition rate [15].

Conclusion:

There is strong evidence in the literature that healthcare worker’s hands get contaminated during their routine work. Without applying proper hand hygiene, this leads to the transmission of infection. Improved hand hygiene reduces infection rates. Putting all together, it can be concluded that hand hygiene is probably the most important intervention for reducing healthcare-associated infections, and preventing the spread of antimicrobial resistance.

Read our previous post on how to handrub and when should we perform hand hygiene.